Rasmus Östling – The Influence of Transcription (Pentiments)

Share

There’s something disarmingly simple about Rasmus Östling’s The Influence of Transcription, and yet I find myself returning to it with the same kind of respect and gentle curiosity I might reserve for an old family photo album - one where the people in the pictures are talking back. The album is an exercise in patient reverence, a kind of slanted homage not only to Fluxus but also to the fragile & intimate gestures that keep memory alive.

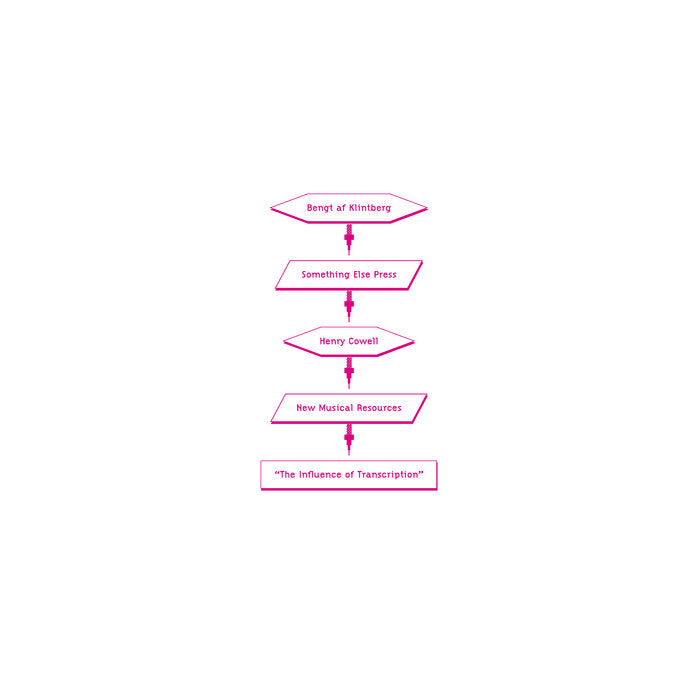

At the heart of it is a recorded conversation between Östling and Bengt af Klintberg, one of the lesser-known but no less essential Scandinavian Fluxus figures. The record plays out like a soft, unhurried walk through a patch of cultural history that has been largely forgotten - at least in the mainstream Scandinavian context. But this isn’t nostalgia. It’s transcription as poetics. It’s archival material as music. The ideas drift, anecdotes shimmer and disappear like dust in backlight, and the very notion of "composition" is pulled apart and reassembled as a kind of documentarian tenderness.

I find it bold that Östling defines this as Archival Music, not because it's sonically radical (it isn’t), but because it pushes against the very function of what we think as music. Music as something meant to be archived, not performed. Something that finds its value in its capacity to exist as record - rather than being a spectacle. I think that’s darn beautiful. As if the whole gesture of this LP was not to say something but to leave behind the possibility of saying. A folder of recorded memory - an anti-monument of some sorts.

To the wholeness of this all the booklet transcription feels rather essential, almost sacred. The object becomes an echo chamber: conversation becomes document —> becomes music —> becomes memory.

I think there is something very courageous about releasing a record like this now in a time where ”experimental music” is often confused with novelty or the said spectacle. Östling’s LP does absolutely nothing to entertain the listener. Instead, it stays close to the ground, to the old dude’s voice, to the act of remembering. It’s humble, funny and conceptually more or less razor-sharp. Östling’s work is for people who understand that sometimes the most radical gesture is simply to listen and then write it down.