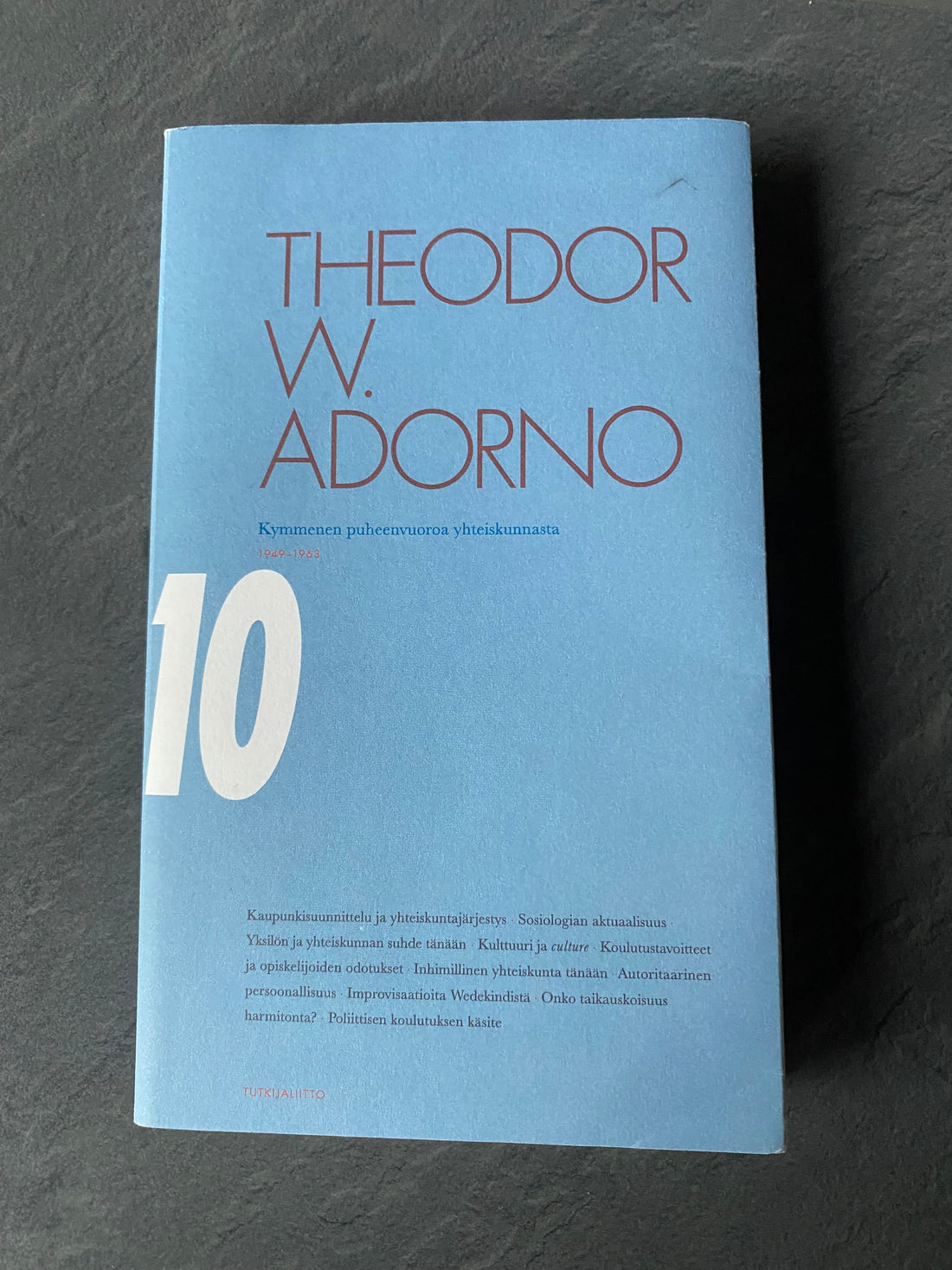

Theodor W. Adorno - Kymmenen puheenvuoroa yhteiskunnasta (Ten Lectures on Society)

Share

It’s not every day that a member of an underground free jazz duo like Pug Life shows up with a serious translation of Theodor W. Adorno. But that’s exactly what Taneli Viitahuhta has done. His recent Finnish rendering of Adorno’s Ten Lectures on Society (Kymmenen puheenvuoroa yhteiskunnasta, published by Tutkijaliitto, 2025) brings one of the 20th century’s most infamously prickly thinkers to bear on our own haunted moment.

At least for me (who is not an academic by a long shot), Adorno has never been, an exactly easy read. His sentences move like tangled branches: beautiful, maybe even sometimes blooming, but rarely straight. Still, there’s a raw urgency in these lectures, delivered mostly in the late 1950s to university students, that translates across time and language. They are not systematic, they’re not written as a treatise or manifesto. Instead, they are more like philosophical interventions — urgent, improvised, often contradictory, but always very engaged. There’s a certain pulse to them, a tension between intellectual depth and irritation.

Taneli’s translation captures that pulse, at least what I can compare to the english translations of Adorno that I’ve skimmed through. And I don’t mean just the linquistic accuracy, though that’s there too rather, he manages to retain the rhythm and general dissonance of Adorno’s speech. This is Adorno the speaker, not just the theorist. Adorno the listener, the critic, the exile returned. And, strangely enough, Adorno the teacher. There's warmth here too, hidden in the crevices of critique.

What’s remarkable about these lectures is how directly they speak to us today. One talks about the “authoritarian personality” — a psychological configuration where submission and aggression co-exist, and which Adorno associates with the rise of fascist tendencies in postwar society. Sound familiar? Heh. Another lecture explores superstition in modern life — not just the usual astrology-and-crystals kind, but the kind that hides in technocratic language, corporate jargon, and the myth of meritocracy. Elsewhere, Adorno critiques urban planning, defends sociology as a radical discipline, and agonizes over the institutional failures of education.

None of this feels dated. If anything, the lectures seem more lucid now than they might have in 1958. They echo through the false neutrality of our algorithmic newsfeeds, the slow-motion collapse of educational ideals, the passive-aggressive PR of capitalist realism. Adorno’s prose is dense because subjects experience of the world is dense. Both commodified and ideological. These lectures cut through that density with rare honesty.

What really strikes me — and maybe this is why I care about this book as more than just a good translation — is the sense of lived critique. Adorno isn’t theorizing from a remove. He’s in it. Frustrated. Grieving. Angry. Occasionally condescending. But always trying to think — and to help others think — against the grain of what society makes feel normal.

Taneli, coming from a background of experimental music, understands this mode of thinking as something intuitive. After all, both experimental music and critical theory share a commitment to resisting closure. In his hands, Adorno speaks with a tone that doesn’t just instruct but stirs. I imagine him pacing, gesturing, going off-script. Not ranting, but performing a kind of dissonant pedagogy.

For those of us working in the fringes — experimental art, small presses and varying underground scenes — this book feels like a quietly explosive tool. It reminds us that theory isn’t a luxury. It’s a necessity, especially when all the bullshit noise around us pretends to be harmony.